Effect of Circadian Preferences and Personality Traits on Academic Achievement in Active Students

Article information

Abstract

Objective

During the past decades, several studies have explored individuals’ differences and their impact on scholarly achievement. The effect of circadian preference and personality on academic performance has been studied in different countries. However, studies have yet to analyze these variables in the Moroccan context (North West Africa) and test whether academic performance relates to circadian types and personality traits. This study aimed to investigate the relationship between those variables in young active students.

Methods

This study included 167 Moroccan active students (age=16.34 years; SD=1.2). The personality trait was measured with Big Five Questionnaire for Children (BFQ-C). We also assessed the circadian typology by using Morningness–Eveningness Questionnaire (MEQ). School grades were used to calculate academic success (grade point average [GPA]). We investigated the relationships between all the parameters.

Results

This study indicates a significant difference in Big Five factors between athlete groups of chronotype. GPA is significantly related positively to MEQ score and openness but negatively to neuroticism. However, no correlation was observed with the other significant five factors.

Conclusion

Professionals must consider circadian preferences and personality traits when looking to facilitate students’ scholarly achievement.

INTRODUCTION

Many studies have investigated possible links between academic performance and individual differences. Biological rhythm and personality traits are also some of these individual differences [1,2]. This biological rhythm, which can change in seconds, includes annual, seasonal, monthly, weekly, daily, and hourly [3]. The most crucial of these rhythms is the circadian rhythm (daily). It affects many human activities, including sleep, cognition, physical school performance, and well-being [4-7]. A large volume of published studies describes it as multidimensional, with the two relatively independent dimensions of morningness and eveningness [8-11]. Morningness–eveningness (M-E) preference can change with age and gender [12-14]. In addition, children are more morning-oriented, and adolescents are more evening oriented [15,16]. Various scales can measure the M-E preferences: the Composite Scale of Morningness [17], Morningness-Eveningness Questionnaire [18], Morningness-Eveningness Scale for Children [19], and Munich Chronotype [1]. The literature has emphasized the importance of chronotype on academic achievement. Recently, researchers have shown that a lower academic performance is related to having an evening type (E-type) [20,21], and adolescents can learn better with more motivation in the afternoon [22]. Other studies consistently show that morning-type (M-type) and academic achievement positively relate to children and university students [23-25]. To explore the relationship between the chronotype and the personality, significant analysis and discussion on the subject are done by using the Big Five Model of personality [26,27]. Indeed, E-type are more extroverted than M-type [28] with a high score on neuroticism [29]. In contrast, M-type is more agreeable [30] and conscientious than E-type, with a positive correlation with stability.

In conclusion, there is evidence for a direct and an indirect effect of chronotype and personality on school performance. Then this study aimed to assess the relationship between school performance with personality and the chronotype.

METHODS

Participants

This study is based on a sample of 167 participants. It represents 54% of students in the same Sidi Taibi high school (Morocco). It is a rural area known for its agricultural activities. Of the participating high school students, 95 were females 72 were males. The mean age was 16.34±1.2 years. All participants were tested in the school schedule and their classroom. All high school students can participate in the study. The data was collected between spring and summer (April–July 2019). The study was approved by the local Ethics Committee (IPR: 0017/2018), and all participants were informed about the experimental design and provided written consent to participate before the intervention. Appropriate ethical standards were followed [31].

Measurement instruments

Academic performances

Grades were taken from the official student database “MASSAR” run by the Ministry of National Education in Morocco, ranging from 0 to 20 in each school subject, with higher values indicating better performance and 10 being the passing grade. Each participant should follow the same course, and all students must take exams in the same form. The overall average is the sum of 11 teaching subjects.

Morningness–Eveningness Questionnaire

Morningness–Eveningness Questionnaire (MEQ) consists of 19 items for self-report. Each field requested the respondents to choose their desired time for sleeping and rising. Each response is assigned a score and is presented on an ordinal scale. Lower scores suggest E-type, whereas higher scores indicate M-type [18].

Big Five Questionnaire for Children

Barbaranelli et al. [32] created the Big Five Questionnaire for Children (BFQ-C), a questionnaire adapted from the BFQ for adults. It consists of five subtests: extraversion, agreeableness, conscientiousness, neuroticism, and openness, which were created to describe the individual. The questionnaire has 65 items with five possible answers, rated from 5 to 1 (5, almost always; 1, hardly ever). We calculated the score for each dimension.

Data analysis

The chi-square (χ2) test was used with Bonferroni correction (p<0.05) to compare the frequencies of categorical variables, so we examined the effect of anthropometrics parameters on the other factors. Analyses of variance (ANOVAs) were performed to find differences in academic performance between chronotype categories. A multivariate analysis of variance (MANOVA) was performed to evaluate whether there are differences in the Big Five scores of students based on circadian preference. The associations between the variables were examined using Pearson’s correlation coefficient. Then we used the partial correlations by controlling the age. All data analyses were performed with SPSS 24 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA).

RESULTS

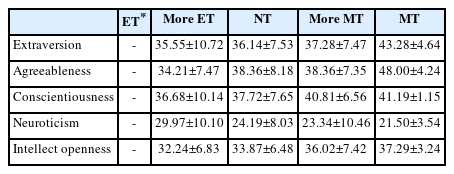

Using the original classification of MEQ [18], our study comprised 51 M-type (31 females, 20 males), 110 intermediates (60 females, 50 males), and 6 E-type (4 females, 2 males). The circadian type difference is insignificant (χ2=2.101, df=3, p=0.552). It can be concluded that sex does not influence circadian typology differences (Table 1). One-way ANOVA (Table 2) revealed that there were no significant differences among the sex in the extraversion score (F=0.352, p=0.554, η2=0.002); agreeableness score (F=1.744, p=0.188, η2=0.010); conscientiousness score (F=1.414, p=0.236, η2=0.008); and intellect openness (F=1.403, p=0.238, η2=0.008). We can therefore conclude that sex does not influence these variables. However, there is a significant difference in the neuroticism score by sex (F=4.220, p=0.042, η2=0.025), and we can conclude that sex influence just this variable of the Big Five model. Table 3 shows a statistically significant difference in Big five factors score between groups of circadian typologies. Indeed, the agreeableness score changed significantly between more ET than MT (p=0.034). Also, the conscientiousness score changed significantly between NT and more MT (p=0.016).

The correlation matrix table (Table 4) presents the correlation between 8 parameters (academic performance, MEQ score, sex, and Big Five factors). We noticed that, out of the 28 coefficients of correlations calculated, 17 relationships were significant, or 60.71%. Firstly, sex is associated negatively with neuroticism (r=-0.158, p=0.043) and grade point average (GPA) (r=-0.29, p<0.001). The academic performance shows 3 (17.65%) significant correlations. Table 4 shows that GPA is significantly related positively to MEQ score (r=0.187, p=0.016) and openness (r=0.208, p=0.007) but negatively to neuroticism (r=-0.218, p=0.005). The MEQ score shows 5 (29.41%) significant correlations. Indeed, the MEQ score is significantly correlated positively with extraversion (r=0.157, p=0.042), agreeableness (r=0.174, p=0.025), conscientiousness (r=0.300, p<0.001), and openness (r=0.251, p=0.001), but negatively with neuroticism (r=-0.159, p=0.04). The extraversion shows 3 (17.65%) significant correlations. Table 4 shows that extraversion is significantly related positively and moderately with agreeableness (r=0.574, p<0.001), conscientiousness (r=0.458, p<0.001), and openness (r=0.460, p<0.001). Agreeableness shows two relationships (11.76%) strongly significant positive correlations with conscientiousness (r=0.445, p<0.001) and openness (r=0.350, p<0.001). The last, conscientiousness, shows two relationships (11.76%): positive correlations with openness (r=0.475, p<0.001) and a moderate negative relationship with neuroticism (r=-0.168, p=0.03). Partial correlations (controlling for sex) between MEQ score and Big Five factors were 0.155, 0.17, 0.297, -0.169, and 0.247 for extraversion, agreeableness, conscientiousness, neuroticism, and openness, respectively (p<0.01, for conscientiousness and openness dimensions). And the correlation between MEQ score and academic performance (by sex control) is 0.181. From Table 5, the correlation between extraversion and agreeableness is more robust in males than females (r=0.699 vs. r=0.493) and between extraversion and conscientiousness (r=0.622 vs. r=0.356). Nevertheless, the correlation between extraversion and circadian typology was significant for males. The link between agreeableness and conscientiousness is more robust in males than females (r=0.586 vs. r=0.323) and between agreeableness and openness (r=0.440 vs. r=0.278). Nonetheless, the other significant correlations are relatively close in intensity.

DISCUSSION

This study verified the association between circadian preference, personality traits, and academic performance among Moroccan high school students. Our results indicate that sex does not influence the circadian typology differences. These results seem consistent with other research, which found no sex differences in the frequency of M-type or E-type [20,33-35]. Although these results differ from some published studies [14,36-39], they found a weak but significant effect of sex on M-type, and women were significantly more oriented to M-type than men. A possible explanation for this inconsistent finding might be that many physical changes during puberty and adolescence [12,40] may change the behavior differently for boys and girls within the family sphere.

Concerning personality traits, we here focus on the concept of the Big Five because it is one of the most widely used conceptualizations of personality [41]. Our study confirms no significant differences among the sex in extraversion, agreeableness, conscientiousness, and intellect openness. However, there is a significant difference in the neuroticism score. These results agree with other research [42,43] findings, which showed females scored significantly higher than males. A possible explanation for these results may be that women have higher levels of anxiety, depression, selfconsciousness, and vulnerability than men. In contrast to other studies [44,45], they found significant gender differences in conscientiousness; again, females scored significantly higher than males. However, other research has found that sex differences were only for neuroticism, agreeableness, and extraversion [46].

The current study found that sex also has an impact on GPA. This finding corroborates the ideas of other research teams [47,48] that confirm girls and women outperform men in academic success, and men outperform women on vocational success criteria. Several possible explanations for this result in our field suggested that girls and boys differ in particular cognitive abilities and school domains [49].

Assessing the relationship between individual differences (biological, psychological) and academic achievement has always been an attractive topic for experts. A fascinating finding in our study was that academic achievement was substantially linked positively with chronotype. This data confirms the hypothesis of the previous studies that confirm that morningness is positively associated with academic achievement and that eveningness has a negative impact [49,50]. In addition, another study performed in Sudan revealed that height GPA was more likely oriented toward the E-type [51], which is also valid for lower school levels [52]. More research confirmed this relationship in different context [21,53-56]. Yet, these results differ from previously published studies [57-60] that revealed academic achievement was not impacted by chronotype.

Our study noted a positive correlation between academic performance and openness and a negative correlation with Neuroticism. However, no correlation was detected for the other Big Five factors. This result seems consistent with other research [61], which found that openness positively correlates with academic performance. Considering the negative association of neuroticism, a possible explanation for these results may be that high neuroticism increases the probability of having test anxiety, which is, in turn, likely to impair performance on class assignments [62,63]. Nonetheless, this hypothesis must be read cautiously because other studies revealed that the higher levels of concern and perfectionism that characterize neurotic individuals might lead to better preparation and higher performance [64,65].

Another finding is intriguing. The circadian preference correlates positively with extraversion, which contradicts previous studies [4,30,66]. They found no significant correlations or weak correlations between morningness and extraversion. However, our result also aligns with other studies [8,67,68]. Circadian preference and agreeableness are correlated positively. This result concurs with Tsaousis’s meta-analysis [69] that found a positive direct link between morningness and agreeableness. However, findings from other studies reported either no relation [66,70] or minor positive associations with morningness [30,67]. The relationship between conscientiousness and circadian preference was positively significant. This finding matches those observed in earlier studies [66,71,72]. Research has repeatedly indicated minor to medium positive associations between them. The link between conscientiousness and circadian preference is the most well-established [29].

Openness showed moderate unique associations with E-type, whereas relations with MEQ score were relatively weak [8,70]. This confirmation is consistent with our finding; others reported moderate positive relations [67] or no significant relation [29]. The relation between circadian preference and neuroticism was correlated negatively. This result contrasts with previous studies [30,66] that found no significant relationship between morningness and neuroticism or may be a positive relationship [70]. Interestingly, when sex was partially out, correlations between GPA, circadian preference, and Big Five scores demonstrated no change, suggesting that the influence of sex on academic achievement, circadian preference, and personality was independent.

This study presents some limitations. First, the small number of the samples—morning- and evening-type students—could limit the results obtained. Second, it is important to note that our study was conducted in a single high school. Therefore, the results should be interpreted with caution, as they may not be applicable to all high schools (in Kenitra). Finally, the study is based on the psychological dimension; the measurement was subjective. Future research has not ignored objective measurements, especially since famous genes control circadian rhythms.

To conclude, chronotype is associated with academic performance and many Big Five personality factors. Future research may focus on another way to measure personality and circadian preferences to compare and confirm the validity of these results. One practical implication may be considering circadian type and personality when looking to facilitate the student’s scholarly achievement.

Notes

Funding Statement

None

The authors have no potential conflicts of interest to disclose.

Availability of Data and Material

The datasets generated or analyzed during the study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization: Anas El-Jaziz, Said Lotfi. Data curation: Anas El-Jaziz, Said Lotfi. Formal analysis: Anas El-Jaziz, Said Lotfi. Investigation: Anas El-Jaziz, Said Lotfi. Methodology: Anas El-Jaziz, Said Lotfi. Resources: Anas El-Jaziz, Said Lotfi. Software: Anas ElJaziz, Said Lotfi. Supervision: Said Lotfi. Validation: Anas El-Jaziz, Said Lotfi. Visualization: Anas El-Jaziz, Said Lotfi. Writing—original draft: Anas El-Jaziz. Writing—review & editing: Anas El-Jaziz, Said Lotfi.