Zolpidem-Induced Sleep-Related Eating Disorder

Article information

Abstract

Zolpidem is widely used worldwide for the treatment of insomnia. However, the sleep-related eating disorder (SRED) caused by zolpidem has recently become a major challenge. The risk of SRED caused by zolpidem is reportedly higher mainly in the elderly, women, and patients with comorbid medical illnesses. There may also be an increased risk in those with a sleep disorder or a family history of sleep disorders. Restless legs syndrome (RLS), obstructive sleep apnea, and sleepwalking could also increase the risk. There are three main hypotheses for the underlying mechanism. The first hypothesis is related to the concentration of zolpidem. Zolpidem is absorbed quickly by the body so as to cause a rapid increase in its concentration, resulting in SRED appearing like delirium. The second hypothesis is a theory related to GABA receptor desensitization, which results in more arousal effects during slow-wave sleep. The third hypothesis is that zolpidem stimulates the brain. The most important treatment is to discontinue the causative drug, which causes SRED to disappear. Reducing the dosage of zolpidem may also improve SRED. Another intervention is to perform a drug switch. Finally, there is a treatment based on the spectrum perspective, in which nocturnal eating is treated by placing SRED and night eating syndrome (NES) at the two ends of a line. Patients appearing closer to SRED on the line require identification and treatment of the underlying sleep problem. We previously reported a SRED patient receiving zolpidem who had RLS. The successful treatment of that patient included administering ropinirole combined with zolpidem discontinuation, indicating that it is important to treat underlying sleep disorders in SRED caused by zolpidem. On the other hand, if the nocturnal eating behavior is closer to NES, such as in patients with few amnesia and eating problems during the daytime, treatments can involving using selective serotonin-reuptake inhibitors, topiramate, and lamotrigine by evaluating mood disorders associated with the eating problem or by focusing on eating disorders.

INTRODUCTION

Zolpidem is widely used worldwide to treat insomnia, for which its efficacy and safety have been recognized [1]. However, the complex behaviors caused by zolpidem have recently become a major challenge. This paper examines the mechanisms and treatments of sleep-related eating disorder (SRED) caused by zolpidem.

SRED AND NIGHT EATING SYNDROME

SRED and night eating syndrome (NES) have nocturnal eating in common with the following characteristics: [2] 1) primarily occurring at night, 2) often being accompanied by insomnia, and 3) being associated with sleep disorders. Hunger and sleep are basic biological desires that are both affected by homeostasis and the circadian cycle [3]. Patients either do not remember at all or remember only some of their eating behaviors that occur during NREM sleep, which corresponds to SRED. However, whether NES and SRED are different diseases or the same disease remains controversial [3]. The two diseases are characterized by frequent waking at night, specific eating behaviors, similar prevalence rates, and being common in young women [4-6]. In addition, both groups of patients are likely to be ashamed of being overweight, having sleep problems, and exhibiting poor food control [2]. On the other hand, there are also differences between the two diseases, the most obvious of which is the level of consciousness NES patients tend to wake up and be fully awake, while SRED patients tend to be at least half or even fully sleep during their nocturnal eating [2]. SRED patients also often have no memory of the eating behavior the next morning [7].

CASE REPORTS ON ZOLPIDEM-INDUCED SRED

Here we present 28 cases of zolpidem-induced SRED (Table 1) [8-19]. The mean age of the patients was 54.8 years, and they comprised 17 females and 11 males. Most of the patients had comorbid sleep disorders such as obstructive sleep apnea (OSA; 13 patients), restless legs syndrome (RLS; 9 patients), sleepwalking (2 patients), and narcolepsy (1 patient). In addition, SRED disappeared after discontinuing zolpidem treatment in most of the patients. All but two of the patients exhibited partial or total amnesia.

RISK FACTORS FOR SRED

SRED caused by zolpidem is reportedly more common in the elderly, women, and patients with comorbid medical illnesses [2]. There may also be an increased risk in those with a sleep disorder or a family history of sleep disorders [3]. RLS, OSA, and sleepwalking could also increase the risk [5]. Thus, clinicians encountering a patient with a sleep disorder or a family history of these sleep disorders should exhibit caution when prescribing zolpidem.

POLYSOMNOGRAPHY OF SRED

One study found that most patients with SRED were awakened during nocturnal eating, with most of them being in slow-wave sleep [20]. The reported frequencies of sleepwalking, periodic leg movements during sleep, and OSA were 50–70%, 25%, and 10–14%, respectively [6,20]. Another polysomnography study found repeated swallowing or chewing during NREM sleep in 29 of 35 patients [21].

CAUSES OF SRED

There are several case reports on SRED caused by zolpidem, which is more common than SRED caused by other classes of drugs, including other Z-drugs. The cause remains controversial. The first hypothesis for the underlying mechanism is related to the concentration of zolpidem. The nature of zolpidem means that it is quickly absorbed by the body [12], and so the concentration of zolpidem can increase rapidly to result in SRED appearing like delirium. Therefore, replacing immediate-release zolpidem with zolpidem CR (comprising immediate- and slow-release components) or reducing the dosage could improve the condition. The second hypothesis is a theory related to GABA receptor desensitization [22]. Immediate-release zolpidem desensitizes GABA receptors more than does zolpidem CR, resulting in more arousal effects during sleep. The desensitization of GABA boosts serotonin to result in brain arousal. The third hypothesis is that zolpidem stimulates the brain [23]. Initial case reports showed that vegetative-state patients temporarily recovered consciousness after zolpidem administration.

A recent prospective study of zolpidem found changes in the brain perfusion of patients in the vegetative state after zolpidem administration [24]. There have also been reports of zolpidem improving poststroke Broca’s aphasia, blepharospasm, quadriparesis of central pontine myelinolysis, catatonia, dementia with apraxia, postanoxic minimally conscious state, bradykinesia, akinesia, dystonia, and post-levodopa dyskinesias [11]. It has been claimed that the cause should be analyzed using a spectrum model [2], to determine whether the condition depends on nocturnal eating being related more to the sleep problem or to the eating problem. Thus, one extreme of the spectrum is mainly associated with the sleep problems accompanied by amnesia, and the other extreme is mainly associated with eating problems without amnesia. Therefore, when SRED occurs, it is necessary to determine whether the patient has more trouble with their sleep problem or with their eating problem.

TREATMENT OF SRED

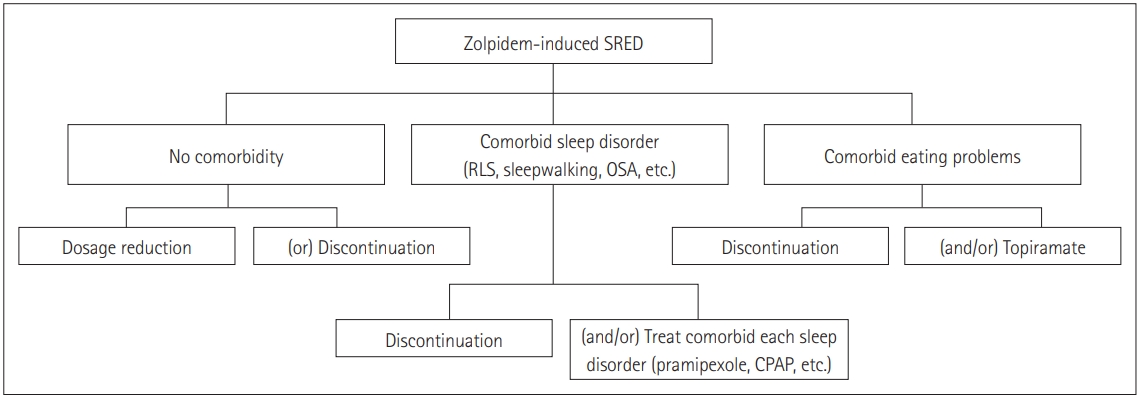

A treatment for SRED has not yet been established. However, some studies suggest the following treatments (Figure 1). One study found that 23 SRED patients reported improvement after taking topiramate [25]. Another study compared pramipexole to placebo, and found that nocturnal eating frequency was reduced and sleep quality improved in the pramipexole group [26]. However, the most important treatment is to discontinue the causative drug [19]. The discontinuation of zolpidem causes SRED to disappear, while reducing the zolpidem dosage may also improve SRED. Dosage reduction might only have a partial effect, including to reduce the hypnotic effect. Another intervention is to perform a drug switch.

Pharmacotherapy for treating zolpidem-induced SRED. RLS: restless legs syndrome, OSA: obstructive sleep apnea, SRED: sleep-related eating disorder, CPAP: continuous positive airway pressure.

Finally, there is a treatment based on the spectrum perspective [2], in which nocturnal eating is treated by placing SRED and NES at two ends of a line. If patients appear closer to the SRED end of the line, the underlying sleep problem needs to be identified and treated simultaneously. We previously reported a SRED patient receiving zolpidem who had RLS, whose treatment included administering ropinirole combined with zolpidem discontinuation [19]. It is therefore important to treat the underlying sleep disorders in SRED caused by zolpidem. On the other hand, if the nocturnal eating behavior is closer to NES, such as in patients with few amnesia and eating problems during the daytime, treatments can involve using selective serotonin-reuptake inhibitors, topiramate, and lamotrigine by evaluating mood disorders associated with the eating problem or by focusing on eating disorders [2,25].

Acknowledgements

This article was supported by a grant from the National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF), funded by Ministry of Education (grant no. NRF-2018 R1D1A1A02085847).

Notes

Conflicts of Interest

The author has no potential conflicts of interest to disclose.