Chronotype Is Associated with Emotional Dysregulation Influenced by Childhood Trauma: A Retrospective Study

Article information

Abstract

Objective

The aim of this study was to clarify the relationships among childhood trauma, emotional dysregulation, and circadian preference in patients with major depressive disorder (MDD).

Methods

This study included 107 outpatients aged between 20 and 65 years who met the criteria of the fifth version of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders for MDD on their medical records. The subjects were divided into morningness, intermediate, and eveningness groups according to their chronotype based on the Korean version of the Composite Scale of Morningness (K-CSM). All of the patients were evaluated using the Korean version of the Mood Disorder Questionnaire (K-MDQ) and the Beck Depression Inventory (BDI). Childhood traumatic events were evaluated using the Korean version of the Childhood Trauma Questionnaire (K-CTQ).

Results

Comparing the demographic and clinical variables revealed that the mean age and the emotional abuse (EA), total BDI, and total K-MDQ scores differed significantly among the three groups. The total K-CSM score was negatively correlated with the total K-MDQ, K-CTQ, EA, and emotional neglect scores. The K-MDQ score was positively correlated with the total K-CTQ, EA, and PA scores. Linear regression analyses were performed to test whether childhood trauma was driving the association with emotional dysregulation (using K-MDQ), and whether emotional dysregulation was driving the association with eveningness (using K-CSM). Both higher EA and total BDI scores were independently associated with a higher K-MDQ score. A higher K-MDQ score was also independently associated with a lower K-CSM score (toward eveningness).

Conclusion

The findings of this study support that childhood trauma influences emotional dysregulation, which in turn leads to a circadian preference toward eveningness. It can therefore be assumed that emotional dysregulation mediates the relationship between childhood trauma and eveningness.

INTRODUCTION

Mood disorder causes abnormalities in biological rhythms [1,2]. In particular, patients with mood disorder exhibit differences in chronotype from the normal population, such as in the circadian preference [3]. A study of the general population found that people with depressive symptoms were more likely to exhibit eveningness than those without depressive symptoms [4]. A study of patients with major depressive disorder (MDD) also found that the frequency of eveningness was higher than that in normal controls [5].

However, not all patients with MDD exhibit eveningness, with both morningness and an intermediate type also being found. This makes it likely that other factors influence the circadian preference of patients with MDD.

This study tested the hypothesis that childhood trauma such as abuse or neglect causes emotional dysregulation and that it acts as a mediator and affects the chronotype. Emotional dysregulation was measured using the Korean version of the Mood Disorder Questionnaire (K-MDQ), whose items seem to reflect not only the experience characteristic of bipolar disorder (BD) but also the emotional dysregulation and risky behaviors that are characteristic of borderline personality disorder [6]. Therefore, the aim of this study was to clarify the relationships among childhood trauma, emotional dysregulation, and chronotype in patients with MDD.

METHODS

This study included 107 outpatients aged between 20 and 65 years who met the criteria of the fifth version of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-5) for MDD at Ilsan Paik Hospital between 2014 and 2018 based on their medical records. Subjects who had psychotic symptoms, any additional mental disorders, or personality disorders according to DSM-5 were excluded. None of the subjects had a history of hypomanic or manic episodes.

The subjects were divided into morningness, intermediate, and eveningness groups according to their chronotype based on the Korean version of the Composite Scale of Morningness (K-CSM), which was derived from the widely used Horne-Ostberg scale [7]. Several studies have demonstrated the good test–retest reliability and adequate external validity of the Composite Scale of Morningness [8,9].

The Korean version of the Childhood Trauma Questionnaire (K-CTQ) is a self-report questionnaire comprising the following five subscales related to the experience of childhood abuse or neglect: physical abuse (PA), emotional abuse (EA), sexual abuse (SA), physical neglect (PN), and emotional neglect (EN). Each subscale consists of five items that are rated on a 5-point scale, from 1 (never true) to 5 (very often true). Depression was evaluated using the Beck Depression Inventory (BDI) and the Korean version of the Mood Disorder Questionnaire (K-MDQ). The K-MDQ was used to identify subjects who were positive for bipolarity or emotional dysregulation.

Analysis of variance or the Kruskal-Wallis test, chi-square test, and Pearson’s or Spearman’s correlation test were used to perform group comparisons according to the properties of variables. Multiple linear regression was used to identify the associations be tween K-CSM, K-MDQ, and K-CTQ scores.

The study protocol was approved by the ethics committee of Ilsan Paik Hospital before beginning the investigation (ISPAIK 2018-10-015-001).

RESULTS

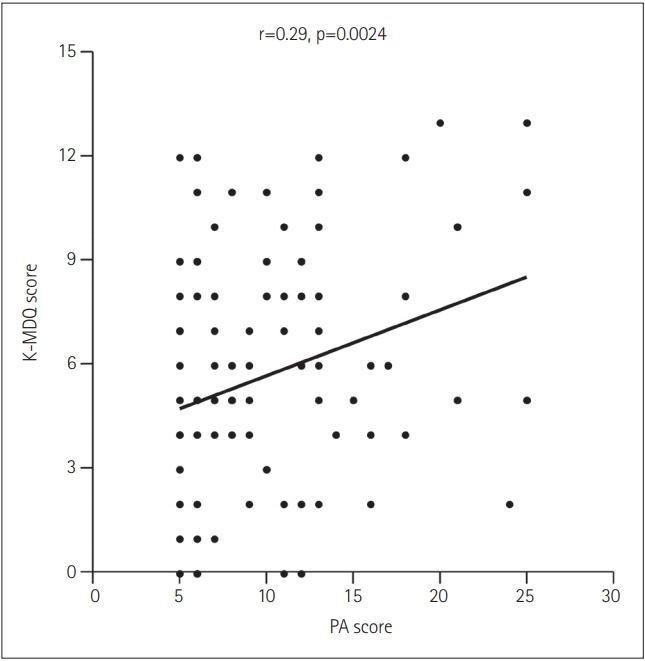

The demographic and clinical variables in the morningness, intermediate, and eveningness groups are compared in Table 1. The mean age and the EA, total BDI, and total K-MDQ scores differed significantly among the three groups, whereas there were no significant intergroup differences in the total K-CTQ, PA, SA, EN, or PN score.

Comparison of demographic and clinical variables between morningness, intermediate, and eveningness patients with major depressive disorder

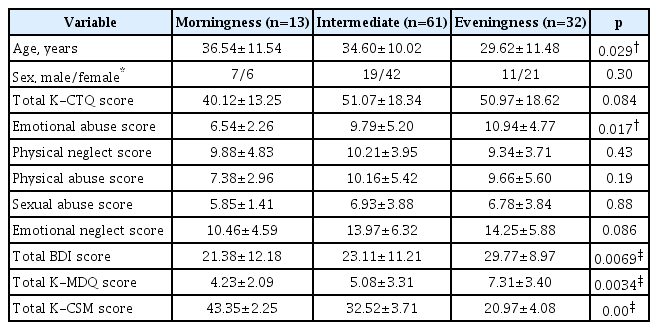

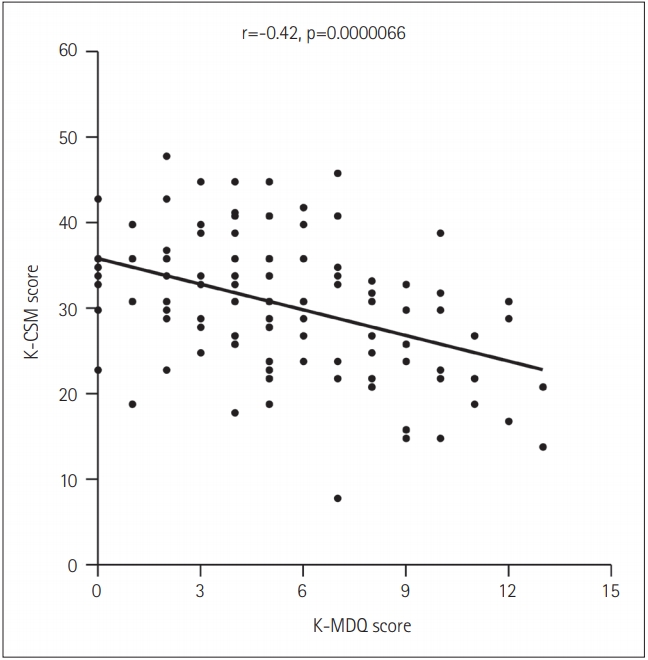

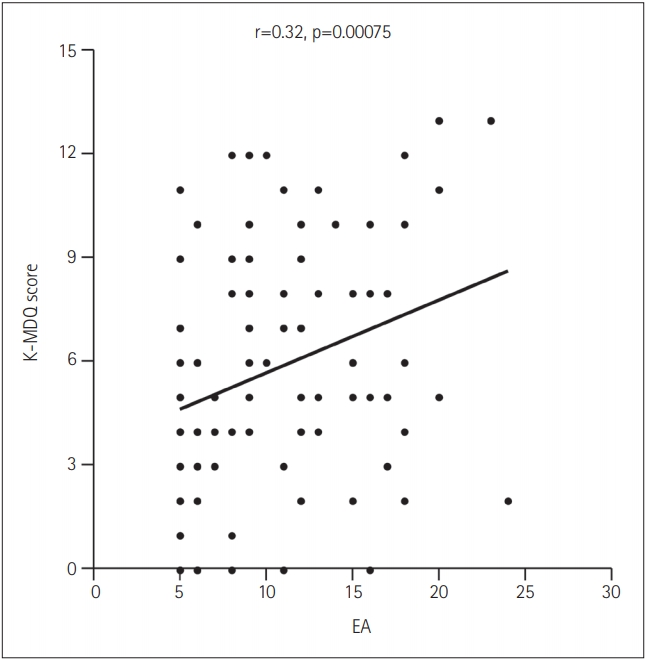

The number of subjects with experience of childhood trauma differed significantly among the three groups (χ2 =6.1, df=2, p= 0.047). In addition, the total K-CSM score was negatively correlated with the total K-MDQ (Figure 1), K-CTQ, EA, and EN scores. The K-MDQ score was positively correlated with the total K-CTQ (Figure 2), EA (Figure 3), and PA (Figure 4) scores.

The correlation between the total K-MDQ and K-CSM score. K-MDQ: Korean version of the Mood Disorder Questionnaire, K-CSM: Korean version of the Composite Scale of Morningness.

The correlation between the total K-CTQ and K-MDQ score. K-CTQ: Korean version of the Childhood Trauma Questionnaire, KMDQ: Korean version of the Mood Disorder Questionnaire.

The correlation between the EA and total K-MDQ score. EA: emotional abuse, K-MDQ: Korean version of the Mood Disorder Questionnaire.

The correlation between the PA and total K-MDQ score. PA: physical abuse, K-MDQ: Korean version of the Mood Disorder Questionnaire.

Linear regression analyses were performed to test whether childhood trauma (K-CTQ) was driving the association with emotional dysregulation (K-MDQ) and whether emotional dysregulation (K-MDQ) was driving the association with chronotype (K-CSM). Both higher EA and total BDI scores were independently associated with a higher K-MDQ score (Table 2). A higher K-MDQ score was also independently associated with a lower K-CSM score (toward eveningness) (Table 2). In contrast, the EA and PA scores were not associated with the K-CSM score, unlike in the correlation test.

DISCUSSION

This study found that childhood trauma influenced emotional dysregulation, which in turn also the chronotype. It can therefore be assumed that emotional dysregulation mediates the relationship between childhood trauma and chronotype. There have been some reports of MDD and BD being related to eveningness [10,11], but the present study is the first to find a relationship between stronger emotional dysregulation in patients with MDD and eveningness.

Many studies have found childhood trauma to have robust negative impacts on clinical outcomes such as earlier age at onset, more severe type, more mood episodes, psychotic episodes, suicide attempts, mixed symptoms or episodes, comorbidity of substance abuse or dependence, and worse life functioning in mood disorder [12-14]. Our results also indicate that childhood trauma aggravates the severity of depression, which is consistent with previous findings [15,16]. In addition, childhood trauma has been reported to cause emotional dysregulation [15,17,18], as also found in the present study. However, there are no previous reports of either emotional dysregulation or childhood trauma influencing the chronotype.

A particularly interesting finding of this study was that higher scores for EA and PA strengthened the association with eveningness. However, there was no significant relationship between EA and PA scores and eveningness when age, sex, emotional dysregulation, and severity of depression were controlled. It can be assumed that EA and PA do not directly affect the chronotype, instead affecting it via emotional dysregulation.

The K-MDQ was originally designed as a screening test for BD [19]. However, the subjects in the current study did not have a history of any (hypo) manic episodes, and some studies have shown that individuals with emotional dysregulation (e.g., borderline personality disorder) can exhibit higher scores on the Mood Disorder Questionnaire [6,20].

In a large Internet-based surveillance study, cyclothymic and euphoric temperaments (which are related to BD) and apathetic, volatile, and disinhibited temperaments (which are related to attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder) were associated with eveningness [21]. In addition, eveningness is associated with less emotional control, coping, volition, and caution, and more affective instability and externalization [21].

The findings of this study support that childhood trauma influences emotional dysregulation, which in turn leads to a circadian preference toward eveningness. It can therefore be assumed that emotional dysregulation mediates the relationship between childhood trauma and eveningness.

Acknowledgements

This article was supported by a grant from National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF), funded by Ministry of Education (NRF-2018R1D1A1A02085847).

Notes

The author has no potential conflicts of interest to disclose.