Gender Differences in the Association between Circadian Preference and Attachment Style

Article information

Abstract

Objective

The present study aims to explore gender differences in the association between circadian preference and attachment style in a community sample.

Methods

A total of 171 community-dwelling adults (98 males and 73 females, mean age=41.06±8.21 years) were recruited. The Morningness-Eveningness Questionnaire (MEQ) was used to measure the circadian preferences, and attachment style was assessed by the Relationship Style Questionnaire (RSQ). The Center for Epidemiological Studies–Depression Scale (CES-D) was used to assess depressive symptoms. The association between circadian preference and attachment style was examined by gender.

Results

The MEQ significantly predicted dismissing attachment (β=−0.254, p=0.001) and fearful attachment (β=−0.177, p=0.016) after controlling for age, gender, and the CES-D score. The MEQ predicted dismissing attachment (β=−0.372, p=0.002) and fearful attachment (β=−0.237, p=0.040) in males, but not in females after controlling for age and CES-D score.

Conclusion

The current finding suggests an association between circadian preference and attachment style, which differed by gender.

INTRODUCTION

The circadian preference, i.e., a preference for morningness (i.e., morning/day activity) or eveningness (i.e., evening/night activity), is an indicator of the circadian rhythm. The circadian preference has been reported to be related to various personality traits [1–3].

Among theories of personality traits, attachment theory posits that caregiving experiences are represented by internal working models (IWMs) [4]. Such IWMs serve as a prototype for future relationships, and influence self-expression and the ability to cope with distressing emotions. Attachment style plays a significant role in understanding how individuals perceive and relate to their world, and could be closely related to an individual’s personality traits. Bartholomew and Horowitz [5] described four types of attachment style, as follows: 1) Secure attachment refers to an infant or adult who does not avoid others and does not feel anxious about being abandoned by others; 2) The dismissing attachment style refers to avoidance of others without feeling anxious about abandonment; 3) In preoccupied attachment, the person places great value on interpersonal relationships because of a great fear of being abandoned by others; and 4) The fearful attachment style describes adults and infants with negative models of the self and others, who show both attachment and avoidance behaviors when abandoned.

Many studies have investigated the associations between circadian preference and personality style, among other psychological factors [6,7]. However, no study has revealed a link between attachment style and circadian preference. Moreover, as previous studies have reported that both circadian preference and attachment style differ between the genders [5,8–13], identifying gender differences in any possible relationship is necessary.

Thus, the present study aimed to explore gender differences in the association between morningness-eveningness and attachment style in a community sample. We hypothesized that circadian preference predicts an individual’s attachment style. We also hypothesized that there would be a gender difference in the relationship between morningness-eveningness and attachment style.

METHODS

Participants

Initially, 207 participants were recruited by advertisements placed in apartment blocks, churches, universities, and a public health center. Data from 171 participants [98 males (47.4%) and 73 females (52.6%), mean age=41.06±8.21 years] were included in the final analysis; 36 participants who did not complete the questionnaire were excluded. No significant difference in age was observed between the males and females. All participants provided informed consent, and this study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of Gachon University of Medicine and Science.

Assessment of morningness and eveningness

The Korean version of the Morningness-Eveningness Questionnaire (MEQ) was used to measure the preference for morningness or eveningness. The MEQ consists of 19 items, with higher scores suggesting a tendency toward morningness [14]. The MEQ classifies respondents into five categories, but no such categorization was performed in this study.

Assessment of attachment style

The Korean version [15] of Relationship Style Questionnaire (RSQ) was used to assess the attachment style of the adults. The RSQ measures four different relationship styles based on Bartholomew’s model, which describes attachment style via the two dimensions of low/high avoidance and low/high dependence [5]. According to Bartholomew’s model, the four attachment styles are: 1) secure (low avoidance and dependence), 2) dismissing (high avoidance and low dependence), 3) preoccupied (low avoidance and high dependence), and 4) fearful (high avoidance and dependence). A higher score on a given subscale indicates that the respondent is better described by it [16]. The RSQ consists of 30 questions, each scored from 0 to 4 points.

Assessment of depression

The Center for Epidemiological Studies–Depression Scale (CES-D) [17] is used to evaluate the severity of depressive symptoms and screens for depressive episodes. The Korean version [18] was used in the present study. This scale consists of 20 items, each scored from 0 to 3 points [6,19].

Statistical analysis

The independent t-test was used to detect gender differences. Pearson’s correlation analysis was conducted to explore the relationships among continuous variables. Regression analysis was used to determine whether there was any association between circadian preference and attachment style after controlling for age, gender, and depression. Three regression models were devised: Model 1 (dependent variable: MEQ score; independent variable: RSQ score), Model 2 (dependent variables: MEQ score, age, and gender; independent variable: RSQ score), and Model 3 (dependent variables: MEQ score, age, gender, and CES-D score; independent variable: RSQ score). The analyses were repeated for each gender. All analyses were conducted with SPSS 22.0 software (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA).

RESULTS

The circadian preference and attachment style of all participants are described in Table 1. The MEQ score was significantly higher in females than males (t=2.458, p=0.015). Among the four attachment styles, the preoccupied attachment score was significantly higher in male than female participants (t=−2.533, p=0.012). The MEQ score was positively correlated with age (r=0.223, p= 0.003). The MEQ score was significantly correlated with higher dismissing attachment (r=−0.226, p=0.003) and fearful attachment (r=0.159, p=0.038). The CES-D score was significantly correlated with higher preoccupied attachment (r=0.223, p=0.003) and fearful attachment (r=0.397, p<0.001).

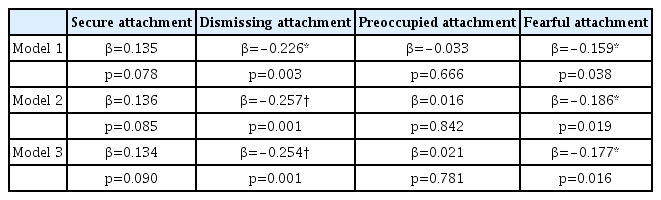

The multiple regression analysis indicated an independent association between the RSQ and MEQ scores (Table 2). In Model 1, the MEQ score significantly predicted dismissing attachment (β=−0.226, p=0.003) and fearful attachment (β=−0.159, p=0.038). In Model 2, the associations of the MEQ score with dismissing attachment (β=−0.257, p=0.001) and fearful attachment (β=−0.186, p=0.019) remained significant after controlling for age and gender. In Model 3, the associations of the MEQ score with dismissing attachment (β=−0.254, p=0.001) and fearful attachment (β=−0.177, p=0.016) were significant after controlling for age, gender, and the CES-D score.

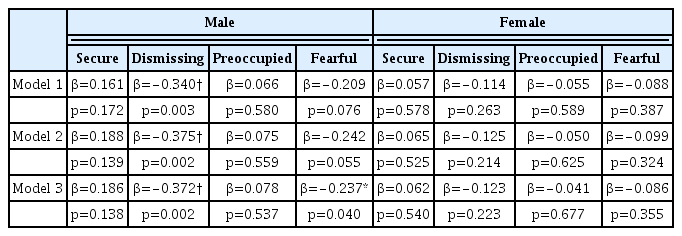

The results of the multiple regression analyses conducted separately for each gender are presented in Table 3. Significant associations between the MEQ and RSQ scores were found only in the male group. The MEQ score significantly predicted dismissing attachment (Model 1, β=−0.340, p=0.003) in males, even after controlling for age (Model 2: β=−0.375, p=0.002), and for age and the CES-D score (Model 3: β=−0.372, p=0.002). In addition, the MEQ score significantly predicted fearful attachment after controlling for age and depression (Model 3) (β=−0.237, p=0.040).

DISCUSSION

The present study was aimed to test for an association between circadian preference and attachment style. Consistent with our first hypothesis, circadian preference predicted attachment style, independent of age, gender, and depression status. Consistent with our second hypothesis, a gender difference was detected in the association between circadian preference and attachment style. An independent association between eveningness and higher dismissing and fearful attachment was only seen in males, and persisted after controlling for age and depression.

The current findings indicate that the circadian preference may have psychological effects, including attachment style. Previous studies have reported significant associations between circadian preference and psychological factors [7]. However, this is the first study to investigate the association between circadian preference and attachment style.

Previous studies have reported gender differences in circadian preference [20] and attachment style [21]. The current study also showed higher morningness and a preoccupied attachment style in males, which supported the gender differences in circadian preference and attachment style.

The present study also showed that dismissing attachment was highly associated with eveningness, even after controlling for gender, age, and depression, suggesting that those with higher eveningness tend to have dismissing attachment regardless of their demographic characteristics or mood. The key traits of dismissing attachment are a lack of interpersonal relationships and emotional indifference [6], and those with the eveningness preference may wish to avoid close relationships during the daytime, instead preferring to be alone during the night.

Fearful attachment was also independently related to eveningness. Individuals with fearful attachment tend to show unpredictable behavior in interpersonal relationships and their judgment criteria are not related to interpersonal relationships [3]. Eveningness is more strongly related to an unstable circadian rhythm and lifestyle compared to morningness [22]. Therefore, unstable traits, such as a fearful attachment style, may be linked to the circadian instability of eveningness.

Additionally, separate analyses by gender showed that the association between circadian preference and dismissing/fearful attachment was present only in males. This gender difference may be related to the higher morningness of females. In addition, females with the eveningness preference may not avoid interpersonal relationships during the daytime or have an unstable life rhythm, as seen in males with the eveningness preference.

Several limitations of this study should also be discussed. First, measuring circadian preference, attachment style, and depression through self-report questionnaires might not fully reflect the characteristics of the individual. Second, the sample size was not sufficiently large to represent the entire population. A future study should include a larger and more diverse sample with respect to age. Finally, the circadian preference does not completely represent biological circadian rhythms in the absence of measurement of biological markers of circadian rhythms, such as melatonin or cortisol.

In conclusion, in the present study circadian preference was independently associated with a specific attachment style. Moreover, there were gender differences in the association between circadian preference and attachment style.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by the Brain Research Program through the National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF) funded by the Korean govoerment (MSIT) (No. 2016M3C7A1904338), National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF) grant funded by the Korean government (MSIT) (No. 2020R1F1A1049200), and the Bio & Medical Technology Development Program of the National Research Foundation (NRF) funded by the Korean government (MSIT) (No. 2020M3E5D908056111).

Notes

Conflicts of Interest

The authors have no potential conflicts of interest to disclose.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization: Seog Ju Kim. Data curation: Seog Ju Kim, Jooyoung Lee, Seahyun O. Formal analysis: Seog Ju Kim, Jooyoung Lee, Seahyun O. Funding acquisition: Seog Ju Kim. Investigation: Seog Ju Kim, Seahyun O. Methodology: Seog Ju Kim, Jooyoung Lee, Seahyun O. Project administration: Seog Ju Kim. Resources: Seog Ju Kim. Software: Seog Ju Kim, Jooyoung Lee. Supervision: Seog Ju Kim. Validation: Jooyoung Lee, Seahyun O. Visualization: Seahyun O. Writing—original draft: Seahyun O. Writing— review & editing: Seog Ju Kim, Jooyoung Lee.