The Association between Eveningness and Alexithymia: Mediating Effect of Depression

Article information

Abstract

Objective

The current study aims to investigate the association of morningness–eveningness with alexithymia, and examine the mediating effect of depression on this association.

Methods

In total, 393 community-dwelling adults (243 females and 150 males; mean age=43.47±14.05 years) were recruited. All participants completed self-report questionnaires including the Morningness–Eveningness Questionnaire (MEQ), Center for Epidemiological Studies-Depression Scale (CES-D), and Korean version of the 20-item Toronto Alexithymia Scale (TAS-20).

Results

Eveningness was independently associated with greater difficulty in identifying feelings in males, but not in females. Depression mediated the association between eveningness and difficulties in identifying and describing feelings in both males and females.

Conclusion

The current study found a direct association between eveningness and alexithymia, as well as a mediating effect of depression on this association. In addition, the independent and direct association between eveningness and alexithymia was more prominent in males than females.

INTRODUCTION

Morningness–eveningness is an individual diurnal preference with respect to daily activity and rest that reflects circadian rhythms [1]. People with greater morningness prefer daytime activities, whereas people with greater eveningness prefer nocturnal activities [2]. Morningness–eveningness has been reported to have a strong relationship with mental health and well-being, as it is greatly affected by the interactions among physiological, psychological, and social rhythms [3]. Previous studies have demonstrated that people with morningness have healthier lifestyles than those with eveningness. In addition, eveningness has been related to depressive tendencies, higher morbidity, poorer health, and low life satisfaction [4-7]. Connections between morningness–eveningness and various psychological and mood problems have been investigated [4-7].

Alexithymia has also been regarded as a contributing factor to various psychosomatic, psychiatric, and substance use disorders [8]. Alexithymia involves difficulty in identifying feelings (DIF) or difficulty in describing feelings (DDF), difficulty in distinguishing between feelings and bodily sensations of emotional arousal, and an externally oriented thinking (EOT) [9] which indicates a tendency to focus on external rather than internal experiences [10]. Alexithymia is characterized by deficits in both cognitive processing and emotion regulation [11,12].

A previous study reported that alexithymia was also correlated with sleep complaints such as insomnia, sleep walking, and nightmares [13]. As sleep is a major behavioral indicator of circadian rhythm, alexithymia may have an association with circadian preferences. However, a previous study reported that the association between alexithymia and sleep disappeared after controlling for depression [13].

Alexithymia is known to be associated with depression [14], and circadian rhythm disruption can also precipitate or exacerbate mood episodes [5,15]. It is plausible that the eveningness affects alexithymia through depression, and that there is direct and independent association between eveningness and alexithymia. However, to the best of our knowledge, the relationships among morningness–eveningness, alexithymia, and depression have not yet been investigated.

We aimed to study the relationship of morningness–eveningness with alexithymia, and the mediating effects of depression on this relationship. We hypothesized that eveningness is independently associated with alexithymia, and that depression has a mediating effect on this association. We also investigated gender differences in the relationships among morningness–eveningness, alexithymia, and depression, as a gender difference in morningness–eveningness has been reported [16].

METHODS

Participants

Community-dwelling adults (age range: 19–79 years) were recruited via posters and brochures placed in churches, apartment buildings, hospitals, and public health centers in the Incheon area of the Republic of Korea. A total of 393 participants (mean age= 43.47±14.05 years) were recruited, including 150 males (mean age=40.35±15.38 years) and 243 females (mean age=45.40±12.81 years). The females were significantly older than the males (t=3.52, p<0.001). There were 48 participants who have mental disorders. The study protocol was approved by the Institutional Review Board of Gachon University of Medicine and Science, and all subjects provided written informed consent.

Instruments

Morningness–eveningness was evaluated using the Korean version of the Horne and Östberg Morningness–Eveningness Questionnaire (MEQ) [17]. Higher scores on this scale indicate greater morningness. The reliability and validity of the Korean version of the MEQ have been confirmed to be acceptable.

The Korean version of the Center for Epidemiological StudiesDepression Scale (CES-D) was administered to all participants [18]. CES-D is a self-report questionnaire with 20 items [19,20]; higher scores indicate more severe depressive symptoms [18].

Alexithymia was measured using the validated Korean version of the 20-item Toronto Alexithymia Scale (TAS-20) [21], a widely used instrument with well-established reliability and validity [21, 22]. The TAS-20 provides a total score and three subscale scores, i.e., DIF (factor 1), DDF (factor 2), and EOT (factor 3). Higher scores indicate more severe alexithymia.

Statistical analysis

The data were analyzed using SPSS 21.0 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA) and PROCESS macro 3.5 developed by Hayes (2020). The independent t-test was performed to compare males and females. Multivariate ANOVAs were also performed to compare MEQ, TAS-20, and CES-D among the five different age groups (20s, 30s, 40s, 50s, and ≥60s).

Pearson’s correlation analyses were performed for continuous variables. For each gender, partial correlation analyses were conducted after controlling for age. Multiple regression analyses were then performed (dependent variables: TAS-20 total and subscale scores; independent variables: gender, age, and MEQ and CES-D scores). To investigate the mediating effect of CES-D score between the MEQ and TAS-20 scores, calculations were performed using PROCESS macro 3.5, template model number 4 [23].

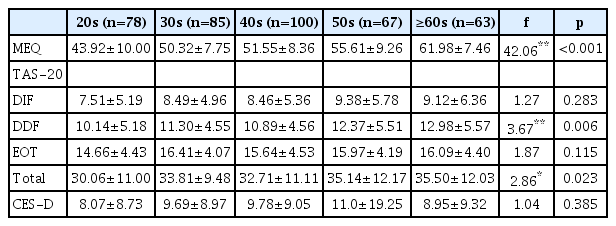

RESULTS

Compared to males, females were older (t=-3.52, p<0.001) and had higher MEQ (t=3.04, p<0.001) and lower EOT (t=-2.43, p<0.05) scores (Table 1). The TAS-20 total, DIF, DDF, and CES-D scores did not differ significantly between males and females. The MEQ (f=42.06, p<0.01) and DDF (f=3.67, p<0.01) scores and TAS-20 total score (f=2.86, p<0.05) were significantly different among age groups, with younger groups showing greater eveningness and less DDF (Table 2). DIF, EOT, and CES-D scores did not differ significantly among age groups.

Age was significantly associated with MEQ (r=0.544, p<0.01), DDF (f=0.163, p<0.01), and TAS-20 total scores (r=0.138, p<0.01). CES-D, DDF, and EOT scores were not correlated with age. The MEQ score was significantly correlated with the DIF (r=-0.120, p<0.05) and CES-D scores (r=-0.140, p<0.01), but not with the DDF, EOT, or total TAS-20 score. The CES-D score was significantly correlated with the TAS-20 total score (r=0.294, p<0.01), and with the scores on all three TAS-20 subscales (DIF: r=0.382, p<0.01; DDF: r=0.209, p<0.01; EOT: r=0.101, p<0.05).

A partial correlation analysis controlling for age was performed for males and females separately. In males, the MEQ score was negatively correlated with the TAS-20 total score (r=-0.267, p<0.01), and with the scores on all three TAS-20 subscales (DIF: r=-0.267, p<0.01; DDF: r=-0.198, p<0.05; EOT: r=-0.170, p<0.05) after controlling for age. The CES-D score was also negatively correlated with the MEQ score in males (r=-0.235, p<0.01) after controlling for age. However, in females, the MEQ score was only negatively correlated with the DIF (r=-0.159, p<0.05) and CES-D (r=-0.200, p<0.01) score after controlling for age. The MEQ score was not significantly correlated with the DDF, EOT, or TAS-20 total score in females after controlling for age.

A multiple linear regression was performed (dependent variable: TAS-20 score; independent variables: gender, age, and MEQ and CES-D scores) (Table 3). For all participants, the MEQ score was a significant predictor of the TAS-20 total score (β=-0.137, p<0.05) and DIF score (β=-0.152, p<0.01). For males, MEQ was a significant predictor of the TAS-20 total score (β=-0.230, p<0.05) and the DIF score (β=-0.189, p<0.05). In contrast, the MEQ score did not significantly predict the TAS-20 total score, or any TAS-20 subscale scores, in females.

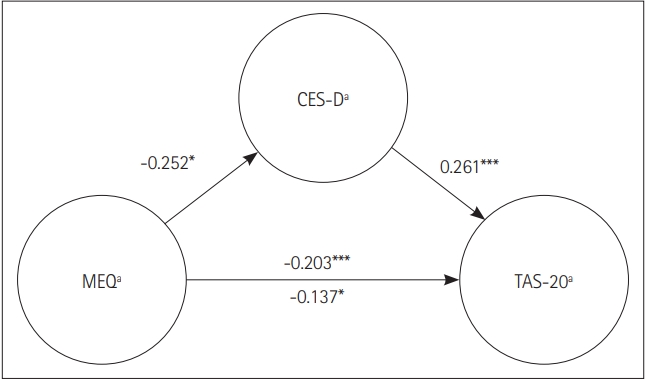

Association of alexithymia with morningness–eveningness, and MEQ and TAS-20 scores, after adjusting for age and gender

A mediation analysis was then performed (dependent variable: TAS-20 score; independent variable: MEQ score; mediating variable: CES-D score) (Table 4 and Figure 1). Given that gender and age were significantly associated with both the MEQ and TAS scores, gender and age were included as covariates in the mediation model. The CES-D score mediated the relationship between the MEQ with TAS-total [B=-0.0718, BI=(-0.1204, -0.0325)], DIF [B=-0.0472, BI=(-0.0756, -0.0233)], and DDF [B=-0.0232, BI=(-0.0429, -0.0078)] scores. In males, the CES-D score mediated the relationship between the MEQ and TAS-total [B=-0.1044, BI=(-0.1907, -0.0325)], DIF [B=-0.0743, BI=(-0.1267, -0.0282)], and DDF [B=-0.0254, BI=(-0.0561, -0.0024)] scores. In females, the CES-D score mediated the relationship between the MEQ and TAS-total [B=-0.0568, BI=(-0.1162, -0.0144)], DIF [B=-0.0341, BI=(-0.0677, -0.0096)], and DDF [B=-0.0229, BI=(-0.0516, -0.0038)] scores. However, the CES-D score did not mediate the relationship between the MEQ and EOT scores, in males or females.

Direct and indirect effects of morningness–eveningness on alexithymia: mediating effects of depression

The mediating model of CES-D between MEQ and TAS20 in total (n=393). *p<0.05, ***p<0.001. MEQ: Morningness–Eveningness Questionnaire, CES-D: Center for Epidemiological Studies-Depression Scale, TAS-20: 20-item Toronto Alexithymia Scale, DIF: difficulty in identifying feelings, DDF: difficulty in describing feelings, EOT: externally oriented thinking.

DISCUSSION

In this study, eveningness was directly and independently associated with alexithymia, especially in males. The relationship between eveningness and alexithymia was mediated by depression independent of gender. Eveningness was related to elements of alexithymia, i.e., DIF and DDF.

Consistent with our hypotheses, eveningness was associated with alexithymia independent of depression, age, and gender. Previous studies have reported an association of depression with both eveningness and alexithymia [14,24]. The association between alexithymia and sleep complaints disappeared after controlling for depression in a prior study [13]. The current study also found that depression mediated the relationship between eveningness and alexithymia. However, we found both indirect and direct associations between eveningness and alexithymia. This partial discrepancy suggests that sleep complaints are more strongly associated with depression than with circadian preferences.

The association between eveningness and alexithymia in the current study may in turn indicate an association between eveningness and psychological traits. Alexithymia has been regarded as a psychological trait that is stable over many years [25,26]. Eveningness is reportedly associated with various psychological and behavioral problems, such as depressive tendencies [15], habitual smoking, and smartphone addiction [27]. People with eveningness might have a tendency to be more immersed in superficialities rather than identifying and expressing their feelings [28,29].

In line with previous studies reporting that people with depressive traits exhibited DIF and DDF [30-32], depression mediated the effects of eveningness on DIF and DDF. These findings suggest that therapists may need to manage depression to encourage clients with eveningness to identify and describe their feeling in the psychotherapy setting.

Interestingly, we found some gender differences in the association between eveningness and alexithymia. Although a mediating effect of depression was found in both genders, a direct and independent association between eveningness and alexithymia was only found in males. This suggests that only depressed females with eveningness are likely to show alexithymia, whereas males with eveningness can be alexithymic whether or not they are experiencing depression.

The current study had several limitations. Frist, the cross-sectional design precludes the identification of causal relationships among morningness–eveningness, depression, and alexithymia. Second, all of the assessment tools were self-report questionnaires. Objective biological indicators of circadian rhythms, such as melatonin, temperature, and cortisol, would be needed to fully elucidate the effects of circadian rhythms on alexithymia.

In conclusion, the present study suggests that people with eveningness, especially males, exhibit a higher degree of alexithymia. The current study also suggests that the association between eveningness and alexithymia is mediated by depression.

Acknowledgements

This research was supported by the Brain Research Program through the National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF) funded by the Korean govoerment (MSIT) (No. 2016M3C7A1904338), National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF) grant funded by the Korean government (MSIT) (No. 2020R1F1A1049200), and the Bio & Medical Technology Development Program of the National Research Foundation (NRF) funded by the Korean government (MSIT) (No. 2020M3E5D908056111).

Notes

The authors have no potential conflicts of interest to disclose.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization: Seog Ju Kim. Data curation: all authors. Formal analysis: all authors. Funding acquisition: Seog Ju Kim. Investigation: Seog Ju Kim, Jihye Ahn. Methodology: all authors. Project administration: Seog Ju Kim. Resources: Seog Ju Kim. Software: Seog Ju Kim, Jooyoung Lee. Supervision: Seog Ju Kim. Validation: Jooyoung Lee, Jihye Ahn. Visualization: Jihye Ahn. Writing—original draft: Jihye Ahn. Writing—review & editing: Seog Ju Kim, Jooyoung Lee.