Circadian Timing of the Female Reproductive System

Article information

Abstract

Precise chronological transition is critical for a normal female reproductive system. Many epidemiologic studies have demonstrated rhythmicity in parturition during the resting phase, and even seasonal breeding. Circadian rhythms are controlled by a multi-oscillatory circadian system. These rhythms are determined by both genetic and environmental factors. The female reproductive axis is also highly rhythmic, and the hypothalamic-pituitary-gonadal axis and the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis are also functional multi-oscillatory circadian systems. Bidirectional communication between the central and peripheral tissue clocks is essential for maintaining the rhythm from ovulation to parturition. This review discusses the circadian timing of the female reproductive system, specifically its underlying metabolic and molecular clock functions. This review particularly focused on the following areas: multi-oscillatory system in the female reproductive system; the ovarian cycle and the timing of ovulation; timing of mating and seasonal reproduction; circadian rhythms in pregnancy; circadian timing of labor onset and parturition.

INTRODUCTION

As the earth rotates, mammals encounter a 24-hour light/dark cycle. Circadian rhythm is a fundamental feature of mammalian physiology that has developed over thousands of years under continuous evolutionary pressure to survive [1,2]. Most organisms on this planet have a clock that serves to anticipate and adapt to environmental demands [3]. The most accepted concept for the mammalian circadian system is a hierarchical multi-oscillator system [4]. There is a central clock within the suprachiasmatic nucleus (SCN) of the hypothalamus, and peripheral clocks have been identified in numerous tissues, including the cerebral cortices, liver, kidney, heart, skin, and retina [5,6]. SCN neurons are circadian pacemakers with the intrinsic capacity to generate an endogenous periodicity of approximately 24 hours in isolation from other neurons [7-10].

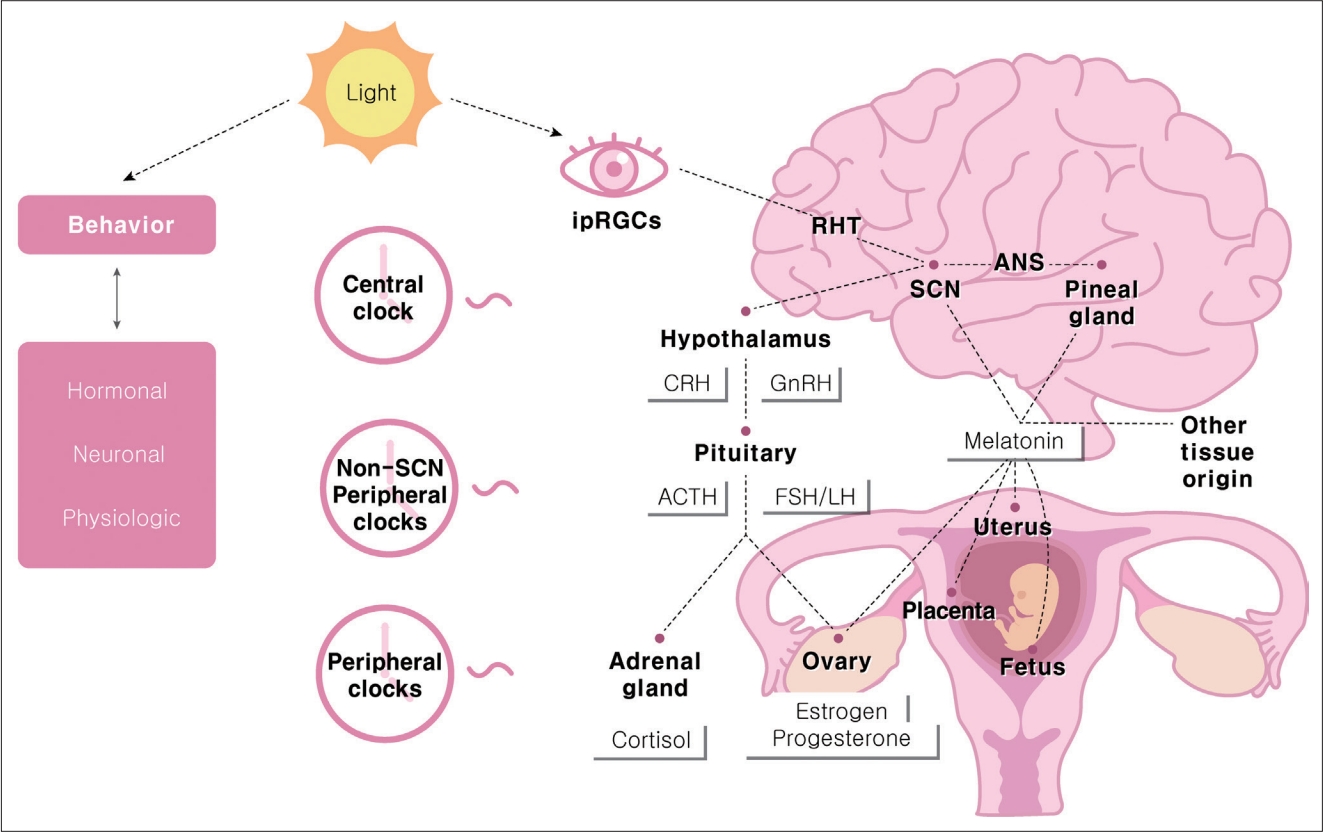

The daily and seasonal circadian rhythms of the human body are controlled through bidirectional communication between the central and peripheral tissue clocks. The main entraining signal is light, mainly through melanopsin-containing intrinsically photosensitive retinal ganglion cells that communicate light directly to the SCN [11]. The SCN sends humoral and neuronal signals to the peripheral circadian tissue [12] and synchronizes the clocks of peripheral organs, including the female reproductive system (Figure 1).

Schematic model of circadian timing system in female reproduction. Light is main entraining signal in circadian timing system. Light from ipRGCs reaches the SCN through RHT. Central SCN clocks transmit the timing information to peripheral clocks along hormonal, neuronal and other physiologic pathways. Non-SCN central clocks, such as melatonin, autonomic inputs acts as circadian oscillator. HPG and HPA axis work as a functional multi-oscillatory system in female reproduction. ipRGCs, intrinsically photosensitive retinal ganglion cells; SCN, suprachiasmatic nucleus; RHT, retinohypothalamic tract; HPG, hypothalamic-pituitary-gonadal; HPA, hypothalamopituitary-adrenal; ANS, autonomic nervous system; CRH, corticotropin-releasing hormone; GnRH, gonadotropin-releasing hormone; ACTH, adrenocorticotropic hormone; FSH, follicle-stimulating hormone; LH, luteinizing hormone.

The molecular basis of these circadian oscillations is an intracellular clock network composed of an autoregulatory transcription/translation feedback loop of molecular clock transcription regulators. In mammals, the core loop includes the transcriptional activator, brain and muscle arnt-like 1 (BMAL1) and its binding partner circadian locomotor output cycles kaput (CLOCK), including the repressors period (PER1/2/3) and cryptochrome (CRY1/2) [13,14]. PER and CRY act as potent repressors of BMAL1: CLOCK-dependent transcription in a negative feedback loop [14]. Almost all reproductive tissues have consistently been described to possess a molecular clock [15].

Successful reproduction, which requires precise timing, is crucial to the survival of a species. In the case of parturition, humans and monkeys (diurnal animals) show peaks in the middle of the night and early in the morning. In contrast, nocturnal animals such as rats and mice give birth in the afternoon [16,17]. To understand these epidemiological results, it is necessary to understand the female reproductive system in terms of the circadian rhythm. This review summarizes the circadian regulation that contributes to determining the timing of female reproduction, emphasizing the role of light and endocrine signals within the female reproductive axis.

MULTI-OSCILLATORY SYSTEM IN THE REPRODUCTIVE SYSTEM

Both the central SCN and peripheral circadian clocks play essential roles in the female reproductive system. The hypothalamic-pituitary-gonadal axis is a functional multi-oscillatory axis. The gonadal function is controlled by a collection of neurons in the hypothalamus that produces gonadotropin-releasing hormone (GnRH). GnRH is synthesized in neurons scattered throughout the preoptic area and the vascular organ of the lamina terminalis. These neurons project to the median eminence, where they release GnRH into the portal circulation in a pulsatile manner to induce proper gonadotropin secretion [18,19].

Current evidence supports the idea that circadian rhythms in kisspeptin neurons might be involved in the control of hypothalamic hormone release in rats. It is also known that other neurotransmitters and hormones, including gamma-aminobutyric acid, glutamate, neuropeptide Y, vasoactive intestinal peptide (VIP), and nitric oxide, play a role. Kisspeptin neurons are located within the hypothalamus in the anteroventral periventricular nucleus (AVPV) and arcuate nucleus. In mammals, kisspeptin neurons are found in the discrete hypothalamic nuclei. The AVPV kisspeptin neurons in particular mediate positive feedback promoting the luteinizing hormone (LH) surge. This contrasts with kisspeptin from the arcuate nucleus, which mediates negative sex steroid feedback [20-23]. GnRH neurons express a kisspeptin receptor (Kiss1R). In females, AVPV kisspeptin neurons are key to the preovulatory surges in GnRH and LH [24-27]. AVPV neurons show circadian oscillations in the expression of the clock genes PER1 and BMAL1, which lie at the core of the mammalian circadian clock [28].

Kisspeptin neurons are activated by a daily signal provided via SCN input. In rodents, environmental light cues synchronize the daily rhythm through the two main neurotransmitters released by SCN, vasopressin, and VIP [29,30]. In the late afternoon, when there are high estradiol (E2) levels exerting positive feedback on kisspeptin neurons, vasopressin activates those neurons, which release neuropeptides to the GnRH neurons, triggering the LH surge in female rodents. Furthermore, Arg-Phe amide-related peptide-3 (RFRP-3) neurons located in the dorsomedial hypothalamus, project to GnRH neurons and inhibit them. Interestingly, although both RFRP neurons and AVPV kisspeptin neurons have daily rhythms of neuronal activity, RFRP neuronal activity is observed not only in the proestrus but also the diestrus stage in rodents [31]. This indicates that RFRP neuronal activity does not depend on circulating E2 levels.

THE OVARIAN CYCLE AND THE TIMING OF OVULATION

Although temporal cues controlled by the central pacemaker (SCN) are essential for driving rhythmicity, secondary clocks located in other central structures and organs play an intrinsic role in reproduction timing. Non-SCN central clocks, such as melatonin, glucocorticoids, autonomic inputs, body temperature, and peripheral clocks, act as circadian oscillators [32].

During the human female follicular phase (metestrus-diestrus in rodents), gonadotrophs produce more follicle-stimulating hormone (FSH) than LH. This relative preponderance of FHS leads to the recruitment and development of ovarian follicles. FSH promotes follicular growth, leading to a progressive increase in E2 secretion and higher LH receptor expression in granulosa cells [33,34]. During this early phase, LH pulses occur with a high frequency (period of 1–2 hours in women). The uniform amplitude and low level of circulating E2 induce negative feedback. However, a marked surge in GnRH and LH secretion occurs, according to the positive feedback of high levels of circulating E2 during the luteal phase in women (proestrus-estrus in rodents). In this phase, the LH pulse frequency decreases to an interval of 2–6 hours with a variable amplitude [35]. A preovulatory LH surge occurs approximately every 28 days in women (4–5 days in rodents). The ovarian follicle is subdivided both anatomically and functionally into mesenchyme-derived theca cells, cuboidal androgen- and estrogen-producing cells that line the outside of the follicle, and epithelial granulosa cells that line the inside of the follicle, surround the oocyte, and primarily synthesize estrogen. Luteinization causes changes in the pattern of steroidogenic enzyme expression in both theca and granulosa cells [36]. GnRH and LH surges trigger ovulation of mature follicles within 24–48 hours in women. The LH surge also recommences oocyte meiosis while arresting granulosa cell proliferation and luteal induction. The timing of ovulation, limited to a temporal window in the afternoon of proestrus, depends on the timing of the LH surge [37,38]. Both hormonal and circadian controls of LH surge timing are necessary for ovulation. The primary role of kisspeptin neurons in reproduction is to stimulate GnRH neurons to release GnRH peptides into the hypophyseal-portal system, promoting pituitary gonadotrophs to release FSH and LH into the bloodstream [39-41].

The LH surge begins in the early morning in women [42] and diurnal (predominantly active during daylight) rodents [43]. However, in nocturnal rodents, the LH surge begins in the early afternoon [44]. Specifically, GnRH and LH surges occur at the end of the night in women [42,45] and diurnal rodents [46], whereas it occurs in the late afternoon in nocturnal rodents [47,48]. As discussed in the previous section, according to rodent studies, the SCN induces a coordinated increase in stimulatory kisspeptin via vasopressin and a decrease in the inhibitory RFRP-3 via VIP to allow a timed LH surge at the end of the resting period. For this precise time control, the core clock genes (BMAL1, CLOCK, PER1/2) and their transcripts are rhythmically expressed in the mature granulosa and luteal cells [49-51].

TIMING OF MATING AND SEASONAL REPRODUCTION

The goal of fertilization is the union of a single selected sperm nucleus with the female pronucleus within the activated oocyte. This requires appropriate mating behavior. In humans, copulation behaviors occur more frequently in the late-night, with a minor peak in the early morning [52,53]. In addition, BMAL1 contributes to maintaining neural circuits that drive pheromone-mediated mating behaviors [54]. The timing of sexual intercourse in relation to ovulation strongly influences the chances of conception. In women, the fertile window lasts approximately 6 days, ending on the day of ovulation [55].

In animals, reproductive activity is restricted to a particular time of the year to address survival environmental challenges. These seasonal reproductive cycles depend on the photoperiod, which indicates the length of the daily light phase. The cyclic melatonin production is the primary cue controlling the onset of breeding. In sheep, which are short-day breeders, changing photoperiod from longer day light to shorter day light with more periods of darkness initiates the reproductive activity. Mating occurs during increasing day lengths (spring), and the breeding season occurs during the short days of autumn and winter. The breeding seasons of hamsters are spring/summer. When female hamsters were exposed to short light period conditions, they became acyclic and anovulatory. They showed an afternoon LH surge and a small FSH increase, suggesting that they were in prolonged proestrus. Therefore, hamsters are also categorized as long day breeders [56]. The duration of elevated circulating melatonin at night depends on night length, with longer melatonin production in short-day conditions than in long-day conditions. Interestingly, when female hamsters were maintained in a long light period and injected with melatonin for several days, their estrus cycle became acyclic, and the pattern of LH and FSH secretion was similar to that found during a long dark period. Taken altogether, it is clear that melatonin plays an essential role in synchronizing seasonal reproductive activity [57].

In adult humans, the synthesis and secretion of melatonin increase shortly after the onset of darkness, with maximal levels usually observed during the middle of the night. Although melatonin is primarily secreted in the pineal gland, enzymes that convert serotonin to melatonin are also expressed in other tissues, including the reproductive tract [58]. Light-induced melatonin suppression is wavelength-dependent, with the highest response induced by short wavelengths such as blue light [59]. The response begins at the retina and is mediated by melanopsin-containing intrinsically photosensitive retinal ganglion cells [60]. Melatonin, whose receptors are present in the SCN, has important effects on neuronal firing and clock gene expression in the central pacemaker [2,61-63]. Melatonin acts at the pars tuberalis of the adenohypophysis to regulate the synthesis of thyroid-stimulating hormone (TSH). During long days, increased TSH secretion leads to higher concentrations of the thyroid hormone T3 that can activate arcuate kisspeptin. This results in GnRH-driven gonadotropin secretion and reproductive activity [34,64].

CIRCADIAN RHYTHMS IN PREGNANCY

Pregnancy, which lasts for approximately 38 weeks after conception, is a complex, multistage process that supports fetal development and optimal delivery [65,66]. For these processes, successful maternal adaptations are required, from marked central modifications in brain function to fundamental changes in reproductive, respiratory, cardiovascular, and metabolic functions [67]. Body temperature, leukocyte count, blood pressure, weight gain, rhythms of uterine contraction, blood flow, and intra-amniotic fluid pressure all follow circadian rhythms during normal pregnancy [68]. According to a recent study in mice [69], the daily activity starting time shifted earlier at the beginning of pregnancy and then back to the pre-pregnancy state approximately one week before delivery. Similarly, by using actigraphy to measure activity level, the time of sleep onset shifted earlier during the first and second trimesters and then returned to the pre-pregnancy state during the third trimester (week 28 until delivery). These results indicate that pregnancy induces changes in daily rhythms. Another more recent study [70] made similar observations also in mice that activity levels decreased during pregnancy, and activity onset was delayed. These behaviors are regulated by the circadian rhythm system.

Endocrine metabolic adaptations are required for maternal circadian rhythms during pregnancy. First, glucocorticoid hormones (cortisol in humans and corticosterone in rats and mice) are powerful mammalian hormonal axes that promote the release of energy stores to meet high fetal demands [71]. Glucocorticoid release is controlled by the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis. There is a multisynaptic neuronal connection between the SCN and autonomic preganglionic neurons that innervate the adrenal cortex, and the adrenal molecular clock regulates adrenocorticotropic hormone (ACTH) steroidogenesis in rhythmic variations [72,73]. The SCN directly and indirectly innervates corticotropinreleasing factor (CRF) neurons, which stimulates the presumed circadian rhythm of CRF secretion and downstream secretion of ACTH and cortisol [74]. ACTH and cortisol concentrations peak in the early morning, coupled with the habitual waking time according to natural light exposure. Levels decline during the daytime in pregnant humans [75-77].

Melatonin is crucial for circadian adaptation during pregnancy. As mentioned above, melatonin affects the timing of hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis activation and mating in animals. Melatonin also acts as a homeostatic hormone during pregnancy, regulating several aspects of fetal physiology. During normal human pregnancy, nighttime maternal serum melatonin levels increase after 24 weeks of gestation, with significantly higher levels from 32 weeks until term [78]. Placenta-derived melatonin directly scavenges free radicals. This process reduces oxidative damage to placental tissues [79,80] and regulates the expression of antioxidant enzymes such as catalase and manganese superoxide dismutase [81]. Melatonin is thought to protect mononuclear villous cytotrophoblasts from apoptosis; therefore, they are able to continuously regenerate to fuse with and maintain a healthy syncytiotrophoblast layer [82,83]. Furthermore, maternal pineal melatonin can even pass through the placenta; therefore, it can be an important factor for entraining fetal circadian rhythms [84,85].

CIRCADIAN TIMING OF LABOR ONSET AND PARTURITION

Parturition is defined by the increasingly frequent uterine contractions accompanying cervical effacement during pregnancy that ultimately lead to the delivery of offspring [86]. Labor begins with the transition of the myometrium from a quiescent to a contractile state. This transition is accompanied by a shift in signaling from anti-inflammatory to pro-inflammatory pathways, involving chemokines (interleukin-8), cytokines (interleukin-1 and -6), and contraction-associated proteins (oxytocin receptor, connexin 43, and prostaglandin receptors) [87]. Since the parturition process requires a secure time and place, most mammals have likely adapted to selective pressures throughout evolution [88].

Parturition occurs at night or during the day depending on the temporal niche of the species. In most animals studied, it occurs immediately before or during the sleep/resting phase. For example, rats deliver predominantly during the subjective day [89-92]. Golden hamsters also deliver in the daytime [93]. Human parturition occurs preferentially at night. According to one retrospective study in the UK [94], labor that starts at night (22:00–06:00) appears to be more efficient than labor that begins during the day (10:00–18:00). Night-onset labor is more likely to result in a “normal” delivery than day-onset labor, undergoing significantly less augmentation with synthetic oxytocin and artificial rupture of membranes. In addition, more normal deliveries and fewer cesarean sections and epidurals are performed during night-onset labor. An Italian retrospective study observed a diurnal rhythm for the onset of labor, with the maximal frequency at night [95]. Similarly, the initiation of labor peaks between 24:00 and 05:00, and births follow after approximately 4 hours [96]. In the case of preterm labor, labor most commonly begins between 24:00 and 06:00 [97]. Even in twin pregnancies, a significant rhythm in the timing of contractions was noted, with 45% of deliveries occurring after labor that commenced between 24:00 and 08:00 [98]. Altogether, labor occurs preferentially during the night in diurnal species and during the day in nocturnal species.

The propensity for nighttime parturition may be related to the synergism between nocturnal increases in melatonin and oxytocin [84,86]. Oxytocin is released in a pulsatile fashion, with maximal levels in maternal plasma reached during the second and third stages of labor; paracrine interactions involving the oxytocin/oxytocin receptor system located in maternal and fetal tissues are important in the initiation of human parturition [99]. However, maternal circulating levels of oxytocin do not significantly increase during labor onset in humans. Instead, they increase more during the final expulsive stage of delivery [88]. Oxytocin receptor expression in the myometrium increases throughout pregnancy, reaching peak levels at the onset of labor. Thus, the uterus becomes gradually more sensitive to oxytocin and is most responsive for the parturition process [100,101].

Pinealectomized female rats, whose endogenous melatonin was eliminated, had normal estrous cyclicity and intact ability to conceive. However, they gave birth randomly throughout the day. Evening administration of melatonin was effective in restoring normal daytime parturition [17]. In an in-vitro study of human myometrial cells, melatonin synergistically enhanced oxytocininduced contractility via the melatonin receptor MT2R [102]. Similarly, melatonin concentration differs significantly in elective cesarean section and emergency cesarean section after induced labor. This suggests that neuroendocrine synergy between melatonin and oxytocin is possible, and that melatonin plays a key role in the onset of uterine contraction [103]. Although MTNR1A and MTNR1B melatonin receptors are expressed in the myometrium of both non-pregnant and pregnant women, MTNR1B (MT2) expression was higher in the myometrium of pregnant women in labor at term [102]. MTNR1B activates the nuclear exclusion of the androgen receptor via activation of protein kinase C [104]; this is similar to oxytocin’s mechanism of action. Therefore, it has been suggested that serum melatonin acts synergistically with oxytocin via the melatonin receptor to membrane-bound phospholipase C and protein kinase C pathways. These pathways promote the expression of the gap junction protein connexin 43 and increase uterine sensitivity to oxytocin, thereby increasing uterine contractility [105]. These findings suggest the reason for the high level of nocturnal uterine contractions that occur during lateterm human pregnancy and result in nocturnal labor.

CONCLUSION

The female reproductive system requires precise timing of processes. Rhythmicity has been demonstrated in ovulation, parturition during the resting phase, and even seasonal breeding. Animals would have needed optimal adaptation for survival and reproduction on Earth. However, recently, the environment has been significantly changing due to artificial light. It has been studied about shift work and night light exposure. It suggested that the female reproductive system could be affected by circadian disruptions. Therefore, understanding the circadian timing of the female reproductive system will be the basis for examining changes in reproductive function due to artificial light exposure.

Notes

Funding Statement

None

The author has no potential conflicts of interest to disclose.

Availability of Data and Material

Data sharing not applicable to this article as no datasets were generated or analyzed during the study.