INTRODUCTION

Melatonin has been used as a relatively safe but moderately effective adjunctive treatment for insomnia [

1]. However, with the recent introduction of prolonged-release melatonin formulations, it has gained approval as a more effective treatment for insomnia compared to traditional immediate-release melatonin [

2,

3]. Several studies have demonstrated its efficacy and safety in primary insomnia [

2,

4]. In a recent paper by the researchers, even when considering prior use of conventional hypnotic medications, prolonged-release melatonin showed significant improvements in sleep onset latency, total sleep time, sleep efficiency, and quality of life compared to baseline after 8 weeks of treatment [

2]. It also demonstrated a high level of tolerability in terms of safety. However, specific analyses of the efficacy of prolonged-release melatonin compared to baseline in treatment-resistant insomnia patients who were still experiencing insomnia despite the use of traditional hypnotics were not conducted in previous studies. Existing research also lacks investigations into prolonged-release melatonin among treatment-resistant insomnia patients who were concurrently using hypnotic medications. Therefore, the objective of this study is to focus on individuals who participated in clinical trials of prolonged-release melatonin for insomnia, and segregate them into two groups: those not taking hypnotic medications for their insomnia and those who are still experiencing insomnia despite using hypnotics. Each group will receive prolonged-release melatonin treatment, with the aim of analyzing the efficacy of prolonged-release melatonin in patients exhibiting treatment-resistant insomnia compared to their baseline conditions.

METHODS

An 8-week prospective, open-label, observational study was conducted on 115 patients aged 55 years or older with insomnia (age range: 55ŌĆō90 years) several years ago [

2]. We recently reported the efficacy of the prolonged-release melatonin using this dataset [

2]. In this study, a post-hoc analysis was conducted on patients who were already taking sleep medication and still reported symptoms of insomnia. The efficacy of prolonged-release melatonin was analyzed using per protocol (n=40) and last observation carried forward (LOCF) (n=63) approaches for this specific subgroup. Additionally, a comparison was made between the subgroup (n=63) of patients who were already taking hypnotic medication for their insomnia and the subgroup (n=52) who were not taking any sleep medication at all. Efficacy of prolonged-release melatonin was assessed using per protocol and LOCF analyses to determine if there were any differences in efficacy between the two groups. The inclusion and exclusion criteria were described in previous our study [

2]. Baseline assessments, including the Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index (PSQI) [

5] and the WHO-5 Well-Being Index [

6] were measured at pretreatment. Subsequently, the prolonged-release melatonin (2 mg) was administered to the patients before bedtime. The sleep indices (PSQI, WHO-5 Well-Being Index) were reevaluated at weeks 4 and 8 to determine improvements in sleep quality. The dosage of prolonged-release melatonin remained at 2 mg throughout the study without any dosage escalation.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analyses were performed based on an intent to treat analysis, and the data included all patients for whom at least a baseline measurement was available. The LOCF method was applied for endpoint analysis. All subjects who received at least one dose of the study medication were included in the safety analysis. In addition, second analysis was conducted using complete analysis. Categorical variables are presented as absolute numbers and relative frequencies (%) and nominal variables as means and standard deviations. Scores on each psychometric scale were analyzed by the Mann-Whitney U test, paired t-test, and repeated measures analysis of variance (RM-ANOVA). The GreenhouseŌĆō Geisser correction was used to test for non-sphericity in RMANOVA. The chi-square test or FisherŌĆÖs exact test was used to analyze categorical variables. All statistical tests were two-tailed with a significance level of 0.05. All statistical analyses were conducted using SPSS software (version 25, IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA).

Ethics

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and Good Clinical Practices. Written informed consent was obtained from all subjects after they had been given an extensive explanation of the nature and procedures of the study. The study protocol was approved by the institutional review or ethics committees at each study site (ISPAIK 2015-10-001).

RESULTS

This study evaluated changes in five sleep indicators in two ways when prolonged-release melatonin was added to insomnia patients who showed treatment resistance despite taking hypnotics.

Per protocol analysis

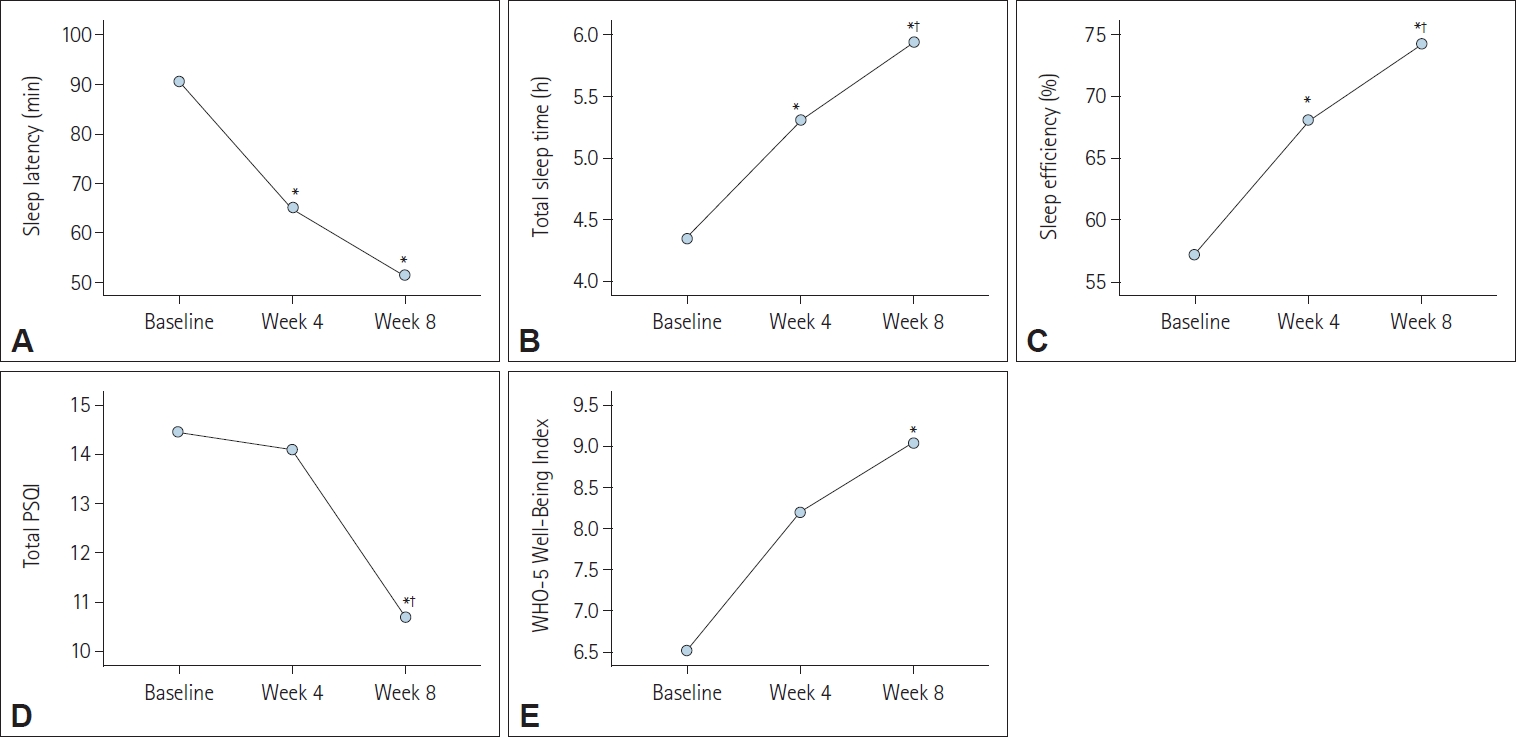

The results of the per protocol analysis indicated significant improvements in four measured variables after 8 weeks of the prolonged-release melatonin treatment compared to baseline except WHO-5 Well-Being Index (

Table 1 and

Figure 1). Specifically, sleep latency and total PSQI revealed a significant decrease over the 8-week treatment period, indicating that it took less time for patients to fall asleep, and their overall sleep quality improved (p<0.01) (

Table 1). Additionally, total sleep time and sleep efficiency revealed a significant increase, suggesting that patients experienced longer and more efficient sleep and reported better sleep quality (p<0.01) (

Table 1).

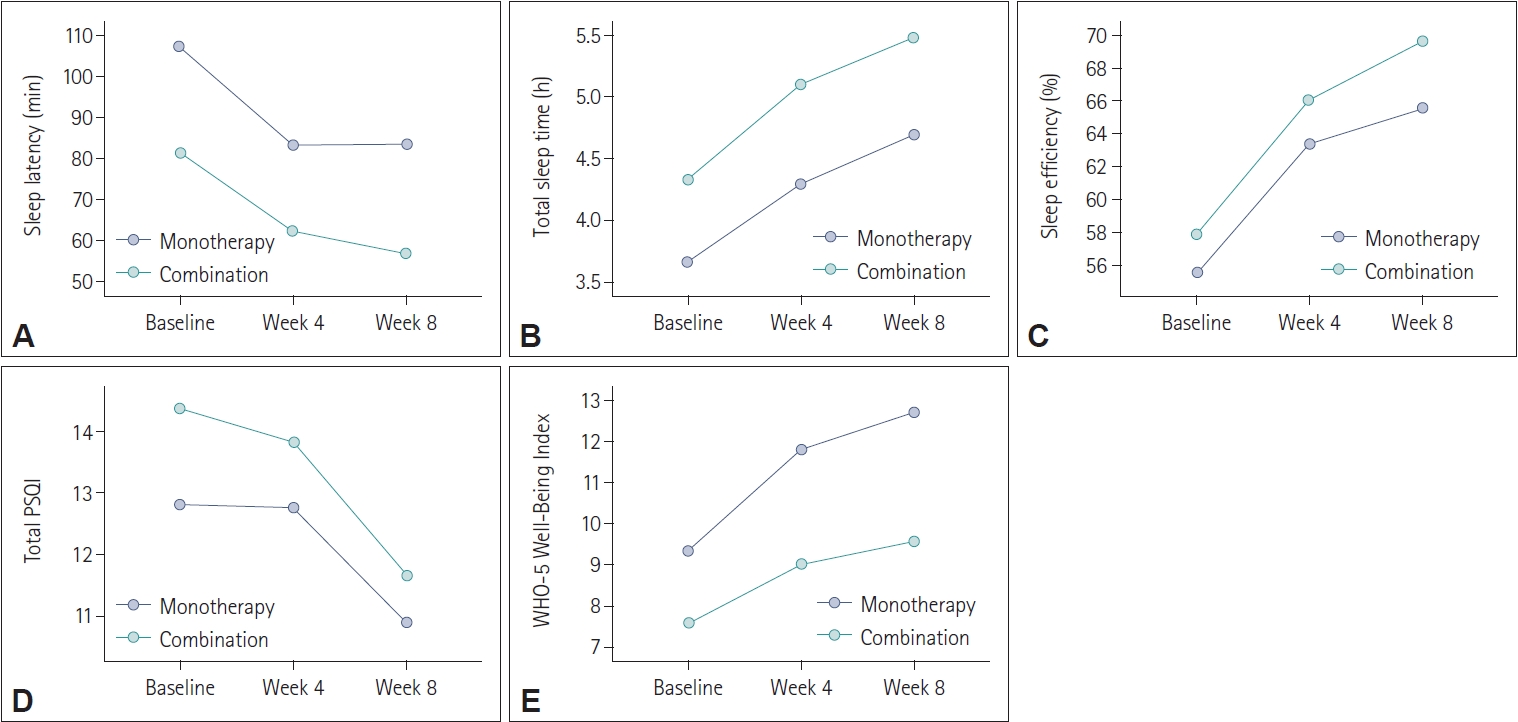

Compared to prolonged-release melatonin monotherapy group with combination therapy group (adding prolonged-release melatonin to previous hypnotics) at baseline, 4 weeks, and 8 weeks after treatment, most variables did not differ between two groups. However, only WHO-5 Well-Being Index was higher in monotherapy group than in combination group at 4 weeks and 8 weeks after prolonged-release melatonin treatment (

Figure 2).

LOCF analysis

The LOCF analysis provided results nearly consistent with the per protocol analysis. After 8 weeks of the prolonged-release melatonin treatment, all five variables showed statistically significant differences compared to baseline (

Table 2 and

Figure 3). Similar to the per protocol analysis, sleep latency and total PSQI demonstrated a significant decrease over the 8-week period, indicating improved sleep initiation and overall sleep quality (p<0.01) (

Table 2). In contrast, total sleep time, sleep efficiency, and WHO-5 Well-Being Index significantly increased, indicating longer and more efficient sleep (p<0.01) and improved well-being (p<0.05) (

Table 2).

Compared to prolonged-release melatonin monotherapy group with combination therapy group (adding prolonged-release melatonin to previous hypnotics) at baseline, 4 weeks, and 8 weeks after treatment, all variables did not differ between two groups (

Figure 4).

DISCUSSION

The per protocol analysis of the study showed several significant improvements in sleep indicators after 8 weeks of treatment with prolonged-release melatonin. Notably, the sleep latency, which refers to the time it takes for patients to fall asleep, showed a significant decrease, indicating improved sleep initiation. Total sleep time and sleep efficiency also demonstrated a significant increase, suggesting that patients experienced longer and more efficient sleep. These improvements are essential factors in alleviating insomnia symptoms and enhancing overall well-being. The fact that these changes were observed in patients who had shown treatment resistance to traditional hypnotics such as benzodiazepines, z-drugs, and trazodone [

7] is particularly promising. Although the definition of treatment-resistant insomnia remains controversial, our subjects reported insomnia despite taking at least one to five hypnotics [

7]. Therefore, this study showed that prolonged-release melatonin has potential as a treatment for patients with treatment-resistant insomnia who do not respond or show partial responses to existing hypnotics. The reason why prolonged-release melatonin, which is known to have relatively weak efficacy, is effective in treatment-resistant patients appears to be largely due to the fact that the current treatment of insomnia is a symptomatic rather than an etiological approach [

8]. Additionally, this suggests that commonly used hypnotics have many limitations in treating insomnia. The reduction in total PSQI scores indicates an improvement in overall sleep quality, which is a critical outcome in treating insomnia. However, it is worth noting that the WHO-5 Well-Being Index, while showing a positive trend, did not reach statistical significance in the per protocol analysis. This could indicate that prolonged-release melatonin may have a more significant impact on sleep-related indicators than on general well-being in this group.

When comparing patients who were already taking sleep medication with those not taking any medication, most variables did not differ between the two groups. However, the WHO-5 Well-Being Index was notably higher in the monotherapy group at 4 weeks and 8 weeks after prolonged-release melatonin treatment. This suggests that while the effectiveness of prolonged-release melatonin in improving sleep indicators was consistent between the two groups, there may be an additional benefit in terms of well-being for those not taking previous hypnotics. This finding was correspondent with previous studies although subjects with insomnia in these studies had breast cancer, chronic renal failure, and delayed sleep phase syndrome [

9-

11].

The LOCF analysis supported the findings from the per protocol analysis, with significant improvements in all five sleep-related variables. The reduction in sleep latency and total PSQI, and the increase in total sleep time, sleep efficiency, and the WHO-5 Well-Being Index all contributed to the overall improvement in sleep quality and well-being. This consistency across analysis methods reinforces the effectiveness of prolonged-release melatonin in this population.

Similar to the per protocol analysis, the LOCF analysis found no significant differences between the combination therapy group (patients already taking sleep medication) and the monotherapy group. Both groups experienced similar improvements in sleep indicators and overall well-being after prolonged-release melatonin treatment. The observed differences in the WHO-5 Well-Being Index between the two groups could be a subject for further exploration. It may suggest that while both groups benefited in terms of sleep, patients not taking previous hypnotics experienced an additional enhancement in overall well-being.

Our study has several limitations. First, the study had a relatively small sample size, with 115 participants. While this sample size was sufficient to provide valuable insights, a larger sample size would have increased the statistical power and the generalizability of the findings. Second, the study utilized a single-arm design, which may limit the ability to draw definitive conclusions about the efficacy of prolonged-release melatonin in treatmentresistant insomnia. A randomized controlled trial with a placebo control group would have provided a more robust basis for comparison. Third, the study included patients aged 55 years or older, leading to potential variability in the etiology and severity of insomnia among participants. Future studies could benefit from more homogeneous patient populations or subgroup analyses to address these variations. However, our findings revealed that prolonged-release melatonin had some efficacy on patients with treatment-resistant insomnia.

In summary, the studyŌĆÖs results clearly demonstrate the efficacy of prolonged-release melatonin in improving sleep latency, total sleep time, sleep efficiency, and overall sleep quality in patients with treatment-resistant insomnia. These findings are consistent across both per protocol and LOCF analyses. The observed difference in the WHO-5 Well-Being Index may warrant further investigation to better understand the potential added benefits of prolonged-release melatonin, particularly in patients not taking prior hypnotic medications. This study provides valuable insights into the use of prolonged-release melatonin as a potential treatment option for this challenging group of patients and paves the way for further research in this area.